The death of Mallett

Something we always did when walking down Bond Street was press our noses against the glass looking in to Mallett’s exquisite showroom. We rarely went in. I suppose relative to the contents and the locked door and the warder at the front, Keith and I felt ourselves the modern day equivalent of Dickensian street urchins, knowing we’d never be able to purchase anything inside, but were nevertheless inclined to see how the other half lived.

Nearly 40 years’ on from our first nose-against- plate glass, and 20 years on from our debut in the trade, we can’t help but feel wistful about the closure of Mallett, and saddened it died such a hard death. For nearly its entire existence since it began in 1865, Mallett has been the ne plus ultra in the trade in English antiques, and certainly for the bulk of the 20th century, the preferred dealer patronized by oil sheiks, international bankers, and, more recently, Russian oligarchs. If one was looking for a bargain, however, it was not to be found there. For us, Mallett’s pricing became something of a yardstick- if we had a similar item in stock, we sought to achieve 25% of Mallett’s sticker.

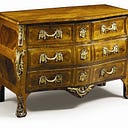

Expensive, yes, but location and reputation and cachet are substantial factors in pricing. As well, in the glory days in the trade in the 1950’s through the 1980’s, Mallett had a long enough purse it could acquire pieces either privately or at auction, salt them away for a few years, and then bring them to buying public as fresh to the trade, with some extraordinary pieces always on offer at the crowning event of the London season, the Grosvenor House fair, itself now only a thing of memory. Quality and condition were always Mallett’s hallmarks, even if those features might have been a bit overdone for collectors. ‘Malletized’ was the sub-rosa term used in the trade for items that might have had a bit more restoration than absolutely necessary.

For many years, Mallett had existed as a public company, and while at one time fairly well capitalized, it nevertheless had to pay out a lot in salaries and occupancy for its locations on Bond Street in London and Madison Avenue in New York, and with declining revenues and changes in taste, could not skinny back its overhead expenses to match declines in revenue. Auction sales of inventory at several times in the last decade, and the sale of its leasehold on Bond Street were quickly gobbled up, and served only as very temporary stop gaps. As well, Mallett’s reputation suffered the embarrassment of having its New York director jailed on fraud charges, the effect of which, frankly, was less severe than it might have been otherwise, given that Mallett overall had by then generally hit the skids. Moving twice in five years to cheaper premises in London, and its purchase by another company clearly have made no difference, with until fairly recently the only thing remaining was the Mallett name. Even that doesn’t appear saleable- erstwhile dealer and auctioneer Mark Law failed a few weeks ago in his attempt to purchase it.

Now, saddest of all, Mallett’s final premises in Pall Mall are now vacant with a ‘To Let’ sign in the front windows. This week’s issue of The Antiques Trade Gazette quotes a terse statement from the company’s current owner Stanley Gibbons Ltd that the space is ‘surplus to requirements’.